iOS 7 wants: Actionable notifications and push interface

By Rene Ritchie

Notification Center debuted in iOS 5 and began transforming Apple’s old, unscalable, modal alert system into something less obtrusive and more robust. Unfortunately, iOS 6 spent so much time setting up the future — kicking Google to the curb, outsourcing social, and improving support for Asia — that notifications were left pretty much at a standstill. Hopefully iOS 7‘s flatter and more consistent redesign won’t occupy the lion’s share of attention this time around, and Notification Center will not only catchup, but leap ahead. And hopefully it’ll start with the transition from informational alerts to actionable ones.

This isn’t a new request by any means. Many people have made it many times,including me last year. Palm had the beginnings of it in webOS, jailbreak apps likeBiteSMS have been doing for ages, and Google started adding it to Android in 2012.

And here’s why — whether we’re tired, busy, or just plain lazy, having to go hunting for apps — even widgets — just to reply to a message, reset a timer, change a song, or do any other trivial activity is outdated and inefficient. It’s pull in the age of push.

It’s well past time for actions, like information, comes to us.

From creation to conversation

In the current version of iOS, if we’re using an app or playing a game or just fiddling around on the Home Screen, and an SMS, iMessage, IM, Hangout, or any other short bit of text is sent our way, we get a roll-down banner notification. If we tap the banner, it rips us from our current activity and sends us carousel-ing into whatever app owns that bit of text. At that point, we have to wait for the host app to wake up, connect, and download the actual message. (Even if all of it was shown in the push notification, the information isn’t passed along and the app has to make its own, post-launch request to get its own, post-launch copy.) Then, after replying, we have to either use the fast app switcher to go back to our previous app, or the old Home button click/icon tap combo. There’s no insta-back button or gesture for that.

Imagine instead that, once the banner notification rolls down, we could not only tap on it to go to the app, but drag it down to get an actionable dialog. Then we could quickly enter and send a response, at which point the dialog would disappear and we could immediately resume what we were doing. No carousel app switching, no need to click and tap our way back.

Apple already does a lot of the out-of-app heavy messaging lifting today, in Share Sheets. Launch the Photos app and pick a photo. Tap the Action button, tap Mail, Messages, or Twitter, and an embedded Mail, Message, or Tweet sheet slides up from the bottom. Type and send a message. The message gets sent and the sheet slides down again, allowing you to continue right where you left off. In fact, Notification Center already has buttons for calling up Twitter and Facebook sheets.

The current system only works to create new messages, and only for Apple’s built-in and integrated partner apps (Mail, Messages, Twitter, and Facebook). It’s not impossible, however, to imagine it working for replies as well.

And with third-party messaging apps. At worst, Notification Center could simply keep pulling the icon to identify the app. In a perfect world, those third-party apps could include parameters for/register with with Notification Center to use in presenting their own embedded sheets (similar in spirit to how Passbook provides for some level of design in third-party passes).

With Notification Center maintaining control of the transactions, communications could be handled more securely and power efficiently as well.

From snooze to choose

The same basic system could also work for changing alarms. Right now, just like with messages, if an alarm goes off, we can either okay it or put it to sleep, but we can’t change it. If we want to do that, we have to mishandle the alert in someway, then go track down the app (typically Clock) to do something about it.

In a push-interface world, the alarm would go off and the banner could be pulled down into, or the popup would already be, a widget that could not only be dismissed or slept, but altered right there and then.

Even if it was kept modal, a timer could be scrubbed back from 00:00 to 00:30, for example, right on the alert.

Likewise, an alarm could be deferred, but could also be quickly changed to another time.

From switcher to center

Controls are trickier, because they’re persistent rather than event-driven. No one wants a constant banner with audio controls in it, for example, which is probably why Apple annexed them into the fast app switcher in iOS 4.

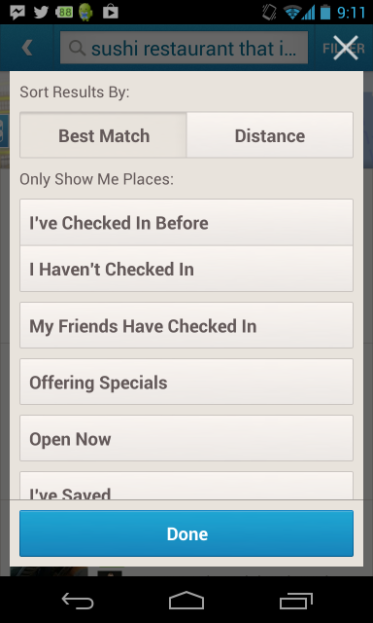

They might make more sense in Notification Center, however, where instead of being a double-click and horizontal swipe away, they’re just a downward swipe. The brightness and AirPlay controls could easily live there as well, as could all the other settings most people never use, but the nerds among us want faster access to — everything from Wi-Fi to Bluetooth to hotspot to Airplane mode, to the kitchen sync in there as well. They could be set to off by default, so mainstream users aren’t bothered by them, but there and ready to be enabled by those who want them.

From static to dynamic

As much as we like to compare platforms and talk about who and who isn’t innovating, who’s blazing ahead, who’s copying, and who’s playing catchup, the truth is every major player is mostly just giving us variations on a theme.

Siri, Google Now, and Kinect are starting to break down the old concepts, not just with natural language and gesture-based control schemes, but with dynamically generated, contextually aware interfaces. They’re still new, still experimental, still layers on top of far more static Home screens, apps, and activities, but they’re getting there.

If Apple wants to get really avant guarde, Notification Center could become contextual, presenting information, actions, and options depending on the time of day, our location, and what we’re doing when we invoke it. And, of course, helpfully nudge us with actionable banners when we haven’t invoked it — the classic example being “Traffic has changed, you will now have to leave 10 min. earlier for your meeting, would you like me to message attendees?”

From the Apple II to the Mac, Apple’s been at the forefront of making ever more accessible types of interface mainstream. Actionable notifications could be a piece of the whatever’s-next puzzle, and I hope we see it from Apple sooner rather than later.

If you’ve used webOS notifications, or Jelly Bean notifications, or BiteSMS, or if you’re just tired of switching apps every time you get an alert, let me know what you think — should the future be actionable, and how?

Source : See Here

You must be logged in to post a comment.